An interview with Thomas Paul Burgess,

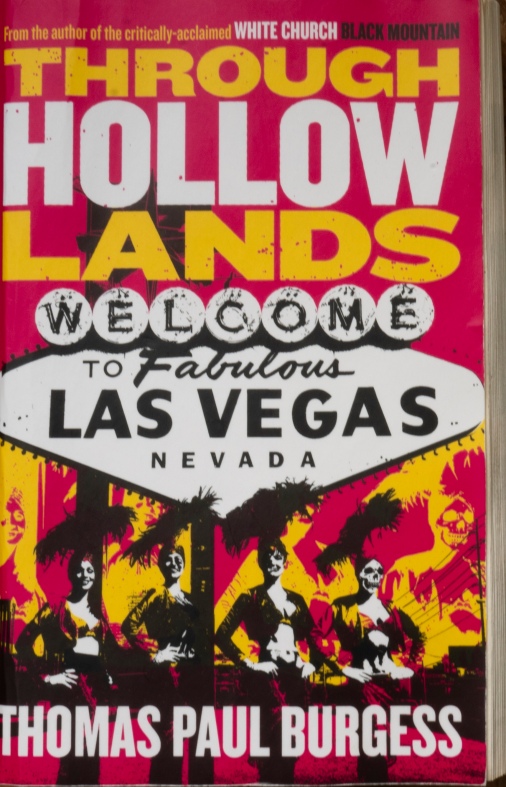

author of Through Hollow Lands by – Urbane Press.

Paul Burgess, punk star, academic and novelist, was back home in the Shankill this week for a dander round old haunts and an interview about his latest novel, Through Hollow Lands.

This book is a study in evil. It is one of the best novels I have read for years.

What I want to know is how a Belfast working-class background leads to this, a book set around the 9/11 attacks on the US. From where does he derive such plausible studies of evil and redemption. Is it because you are a Protestant?

Well, sort of.

One might as well ask, however, how such a start in life, in a two-bedroom house in Jersey Street, to parents who had had minimal education, led to him being a drummer and songwriter for the punk band Ruefrex and what would take a man on from there to doing his Masters degree in Oxford and now being a lecturer at Cork University.

It all seems so unlikely.

As for why the book is set around the 9/11 attacks, Burgess says that he had a near miss. He had made a last-minute dash to board a plane to Las Vegas, while on a fly-and-drive holiday with his wife, torn between that option and Flight 93 to San Francisco.

The lightness with which they made that decision saved their lives. They woke up in their Las Vegas Hotel room to a call from home to check that they were safe. Then he turned on the television.

They saw the Towers fall and learned that they were to be stuck in Las Vegas. No flights were taking to the air at all.

And that sets the basis of the story in his book.

“It was surreal.”

My well thumbed copy

The twist that unfolds, however, is that Las Vegas, for lead character George Bailey is not what it seems.

Bailey is the sort of man it is easier to describe with expletives. He is a worthless liar and a cheat.

Good women have loved him and suffered for it.

We meet them in the book too.

But as George’s journey takes him deeper into Hell we see that he is by not the worst that a human being can be.

And there are angels who even now seek to redeem him.

There are people — and he has crossed them — for whom the depths of evil are the only redemption they can conceive of, for whom wisdom comes with loss of innocence.

But George Bailey has been given a second chance. His Las Vegas is a sort of purgatory, in which the sins of his past revisit him and he has a second chance.

The echo here, of course, is with that other George Bailey, played by James Stewart in A Wonderful Life, who is given a vision of how much worse off the world would be without him. In Through Hollow Lands, George is shown how much worse the world is because of him.

I put it to Paul Burgess, this is religious thinking.

“I have often wondered if human beings are fundamentally good, but capable of great evil, or fundamentally evil, but capable of great good,” he says. “As I grow older, I begin to think it’s the latter.”

Original sin. The fallen state.

“Yes.”

But he also says the book can be read as a comment on modern America.

“It’s ultimately about the redemption of the United States, because the main political premiss that runs through it is how America has fallen from grace, fallen away from the American dream. And my belief is that the catalyst for that was 9/11.

“And so, while the rest of the novel is about a wrestling match for the soul of George Bailey, it is also for the soul of what the American dream is supposed to be about.”

Burgess failed his 11-Plus and went to the Boys’ Model in Ballysillan. He demonstrated an interest in reading and a teacher encouraged him to do exams.He took a job as a clerk in Shorts and finished A-levels at night classes.

One consolation in this struggle was his love of drumming.

“The first time I played drums was in the Pride of Ardoyne Flute band, when I was 16. It was a genuine community thing. A lot of my buddies were in the band. It was a good way to meet girls.”

But the fit was not a good one, between his growing political awareness and the wider culture of loyalism.

“After about a year, it was plain that a lot of the associated culture was inconsistent with my emerging political analysis, which is that there are aspects of this triumphalism that I can’t sanction and don’t want to be part of. So I walked from that.”

He formed Ruefrex with other local boys. With Tom Coulter, a bass player, they made a single with Terry Hooley. It got played on Radio 1 by John Peel.

“And you couldn’t put a price on that at the time. Write-ups in NME.”

Playing one night at the University of Ulster he saw the attractions in being a student, so caught up again with education, only to find himself behind again.

His peers had moved on before he got in.

But he enjoyed his studies of literature and graduated, only to find himself back in the Boys’ Model and other Shankill schools as a supply teacher. This was going to be rough.

He had one boy tell him he would get his da’ up to shoot him and even had to put on a bit of swagger to counter threats like that.

“Then word went round that Burgess is connected and I enjoyed that for a time and then got sick of it.”

He faced a tension between being part of a working-class Protestant community but not a monarchist, or a loyalist.

“I variously went through stages of being apologetic and, as I moved into bourgeois, middle-class circles and then flipping and saying my community is as entitled to a cultural expression as anybody else’s and just because it doesn’t tick a lot of the boxes that are currently politically correct, I’m not sure that that’s enough.”

A chance came to go to London, sleep on floors, revive the band, make albums.

In a very short time he was successful beyond his dreams, being played on daytime radio.

For a time in London, the music Press liked the idea that he was from the Shankill and made him out to be an extremist, often contrasting Ruefrex with a band from Derry, That Petrol Emotion.

You can still see him looking stiff and formal in his white shirt and moustache on old videos, hammering out the beat to the Wild Colonial Boy, not the traditional version, but a sneering parody on the attitude of the Irish American who supports the IRA. The song ends with the words: “It really gives me such a thrill/to kill from far away.”

But success wasn’t going to last, forever. He saw himself being a teacher again and decided to get properly qualified, applied to Oxford, since there was nothing to lose, and to his surprise got in.

Then he taught a year in Chipping Norton and went back to Oxford to do a Masters degree by research on Integrated Education in Northern Ireland.

He has great stories about that time and later that are not in the books.

A hate figure for him — perhaps a study in evil — is a former headmaster who suspended him and made him bring his parents into school and humiliated them.

He believes in class-based politics, a perspective drawn from his mother’s work in a clothing factory owned by Brian Faulkner, the former Northern Ireland prime minister, and his brother.

He recalls the deference shown to the Faulkners. Years later, after Oxford, he was working on the Opsahl Commission, a project to assess the prospects of peace in Northern Ireland, when he received a message that Lady Lucy Faulkner wanted him to call on her.

Intrigued, he visited her at home.

She had a job for him. She wanted him to move some boxes.

“I told Davy Ervine that story, God rest him, and he got a great laugh out of it.”

This article was first published in The Belfast Telegraph, September 15, 2018

I have already saved myself a bit of work and possible embarrassment with

I have already saved myself a bit of work and possible embarrassment with